Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Good habits can change your life, but most people struggle to build them consistently. That is the exact problem Atomic Habits by James Clear tries to solve. The book explains why habits fail, how to fix them and how small steps can compound into major change. This summary walks you through the main ideas of the book so you can pick up the core lessons without reading it cover to cover. The goal is to give you a clear, practical understanding of how habits actually work and how you can redesign them to support your goals.

James Clear is a writer, speaker and productivity expert known for simplifying complex ideas. His work focuses on human behavior, habit formation and continuous improvement. He started by sharing weekly newsletters on building better habits before publishing Atomic Habits, which went on to become a global bestseller. His ideas are influenced by scientific research, psychology and his own personal recovery journey after a severe injury in childhood.

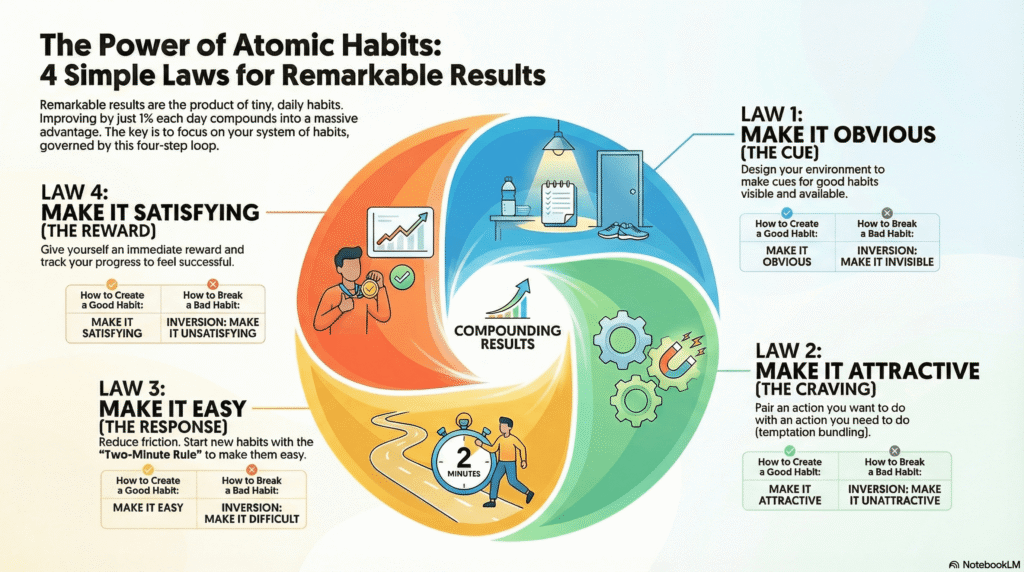

The core philosophy centers on the “aggregation of marginal gains,” or the idea of seeking a tiny margin of improvement in everything you do. Improving by just 1 percent each day for one year results in becoming nearly thirty-seven times better by the end, illustrating the astounding difference small improvements can make over time. Conversely, a 1 percent decline daily leads to falling nearly down to zero.

Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement; their effects multiply as they are repeated over months and years, becoming enormously impactful.

The author shares his own story of recovery and eventual success in college baseball, emphasizing that his progress came not from a single moment but from a gradual evolution—a long series of small wins and tiny breakthroughs, proving that changes that seem unimportant at first will compound into remarkable results if one sticks with them.

This realization leads to a shift in focus: forget about setting goals and focus on your system instead. Goals are about results, while systems are about the processes that lead to those results. Focusing only on goals presents problems: winners and losers often share the same goals, achieving a goal is only a momentary change (you must change the system behind the result), and goals can restrict happiness by constantly putting satisfaction off until the next milestone.

True long-term thinking is goal-less thinking—a commitment to the cycle of endless refinement and continuous improvement. You do not rise to the level of your goals; you fall to the level of your systems. An atomic habit is defined as an extremely small amount of a thing and the single irreducible unit of a larger system, which is also the source of immense energy or power. Atomic habits are the building blocks of remarkable results.

Changing habits effectively requires changing not just the outcomes (results) or processes (systems), but the identity (beliefs). Most people focus on outcome-based habits (what they want to achieve), but the alternative, identity-based habits, starts by focusing on who you wish to become.

When behavior and identity are fully aligned, you are simply acting like the person you already believe yourself to be, making the right thing easy. True behavior change is identity change.

The process of changing identity is a two-step process:

(1) Decide the type of person you want to be, and

(2) Prove it to yourself with small wins. Your identity emerges from your habits, with every action being a vote for the type of person you wish to become.

The process of habit formation can be broken down into a neurological feedback loop of four simple steps:

This cycle—Cue, Craving, Response, Reward—is known as the habit loop. If any step is insufficient, the behavior will not become a habit.

The four steps lead to the Four Laws of Behavior Change for building good habits, which can be inverted to break bad habits:

| How to Create a Good Habit | How to Break a Bad Habit |

| 1st Law: Make it Obvious | Inversion: Make it Invisible |

| 2nd Law: Make it Attractive | Inversion: Make it Unattractive |

| 3rd Law: Make it Easy | Inversion: Make it Difficult |

| 4th Law: Make it Satisfying | Inversion: Make it Unsatisfying |

The process of change must begin with awareness. Since habits often become nonconscious and automatic, techniques are needed to recognize the cues that trigger them.

To start a new habit, one must create obvious cues:

The environment profoundly shapes human behavior. Small changes in context can lead to large changes in behavior. To design an environment for success, make the cues of good habits obvious and visible. Conversely, the Inversion of the 1st Law (Make It Invisible) is the most practical way to eliminate a bad habit by reducing exposure to the cue that causes it.

The more attractive an opportunity is, the more likely it is to become habit-forming. Habits are a dopamine-driven feedback loop; dopamine rises not just when pleasure is experienced, but when it is anticipated, motivating action.

The Inversion of the 2nd Law (Make It Unattractive) is achieved by reframing one’s mind-set and predictions. Since underlying motives drive specific cravings (e.g., wanting tacos to fulfill the need to obtain food), you can reprogram your brain by associating hard habits with a positive experience, such as shifting language from “I have to” to “I get to”. You can also highlight the benefits of avoiding a bad habit to make it seem unattractive.

The 3rd Law is to Make It Easy. Our natural tendency is to follow the Law of Least Effort, gravitating toward the option that requires the least amount of work.

The Inversion of the 3rd Law (Make It Difficult) involves increasing friction for bad habits. This can be achieved through commitment devices (a choice made in the present that controls future actions) or automating your habits with technology and one-time purchases to lock in future behavior (e.g., setting up automatic bill pay or deleting social media apps).

The 4th Law is crucial because it ensures a behavior will be repeated next time, thus completing the habit loop. The Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change states: What is immediately rewarded is repeated. What is immediately punished is avoided. Because modern society is a delayed-return environment, our brain, which evolved for immediate-return environments, struggles with delayed gratification.

To make good habits immediately satisfying:

The Inversion of the 4th Law (Make It Unsatisfying) involves adding an instant cost to bad habits. An accountability partner or a habit contract (a formal agreement outlining consequences for failure) introduces a social cost, making violation immediately painful and public.

To go from good to great, habits must be combined with deliberate practice. Mastery requires progressively layering improvements and continuously refining skills, since automatically repeating a habit can lead to complacency and reduced sensitivity to feedback. The most successful people find ways to handle the boredom of training every day.

Motivation is maintained by adherence to the Goldilocks Rule, which states that peak motivation occurs when working on tasks that are right on the edge of current abilities—not too hard, not too easy. This keeps the behavior novel and engaging, countering boredom, which is “perhaps the greatest villain on the quest for self-improvement”.

Finally, top performers use reflection and review to remain conscious of their performance, ensuring habits improve rather than decline. Reflection allows one to determine if current habits and beliefs are still serving one’s desired identity.

Ultimately, the path to results that last is to never stop making improvements. The holy grail of change is not one single improvement, but a thousand atomic habits stacking up.