Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Money touches every aspect of our lives, yet few subjects are as misunderstood. We obsess over spreadsheets, investment strategies, and market predictions while ignoring the psychological forces that truly drive financial success.

Morgan Housel’s “The Psychology of Money” flips traditional finance advice on its head. Instead of focusing on what to do with money, it examines how we think about money. Published in 2020, this book has become a modern classic, resonating with millions who recognize that financial success has more to do with behavior than intelligence.

The book’s central premise is simple but powerful: doing well with money has little to do with how smart you are and a lot to do with how you behave. Through 19 short chapters filled with engaging stories and timeless wisdom, Housel reveals why managing money is fundamentally about managing human psychology.

Affiliate disclosure: We earn a commission if you click our links and make a purchase – it will not cost extra to you, but it will encourage and support this blog site in great deal. Prices and availability checked November 2025.

Morgan Housel is a partner at The Collaborative Fund and a former columnist at The Motley Fool and The Wall Street Journal. His work focuses on the intersection of psychology, behavior, and finance.

Housel has won numerous awards for his financial writing, including two-time winner of the Best in Business Award from the Society of American Business Editors and Writers. He studied economics at the University of Southern California and has spent over a decade analyzing how people think about money.

His unique perspective combines academic research with real-world storytelling, making complex behavioral finance concepts accessible to everyone. Before writing this book, his articles reached millions of readers who appreciated his clear, thoughtful approach to financial wisdom.

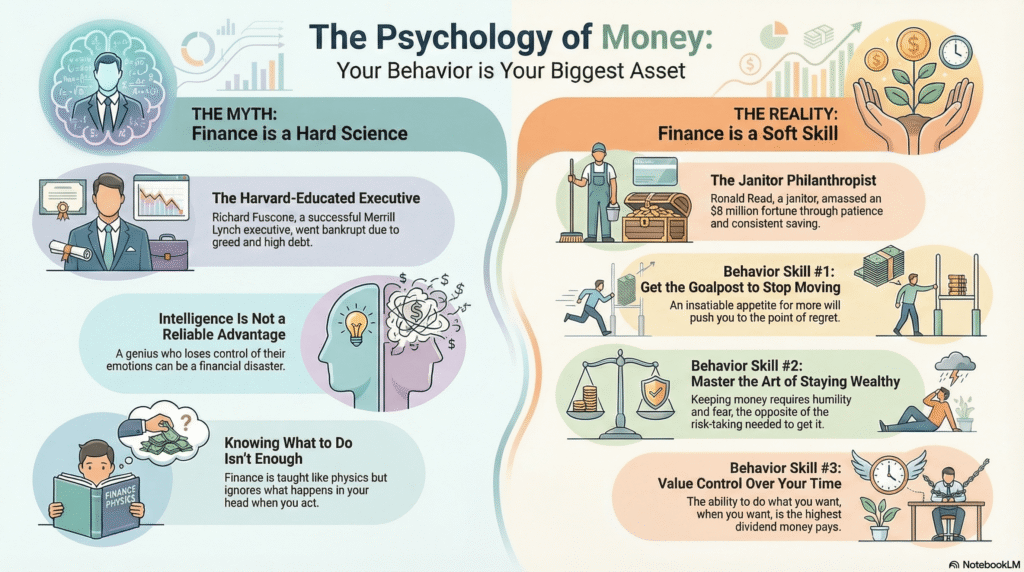

The overarching premise of the book is that doing well with money has little to do with how smart one is and a lot to do with how one behaves. Because behavior is often difficult to teach, even to brilliant people, financial success is more accurately described as a soft skill—the psychology of money—rather than a hard science governed solely by math and formulas. While knowledge of financial concepts is important, knowing what to do tells one “nothing about what happens in your head when you try to do it”.

The importance of behavior is starkly illustrated by contrasting the outcomes of highly educated executives with those of humble individuals.

A successful but emotionally erratic technology executive, a genius who designed a key component in Wi-Fi routers, carried thick stacks of cash, bragged loudly, and once threw thousands of dollars in gold coins into the Pacific Ocean just for fun. Despite his brilliance and early success, he lost control of his emotions and eventually went broke. In contrast, Ronald James Read, a janitor and gas station attendant, lived a low-key life in rural Vermont. Read saved whatever he could and invested it patiently in blue-chip stocks for decades. When he died at age 92, his tiny savings had compounded into more than $8 million, which he left primarily to his local hospital and library. Similarly, Richard Fuscone, a Harvard-educated Merrill Lynch executive, retired wealthy in his 40s but borrowed heavily to maintain an opulent home and subsequently went bankrupt in the 2008 financial crisis. The author concludes that Read’s patience eclipsed the massive educational and experiential gap between him and Fuscone, demonstrating that financial success is often determined by temperament (such as patience versus greed).

The first lesson of the psychology of money is that “no one is crazy”. Everyone, born into different generations, economies, and circumstances, learns unique lessons about how money works. Because what one has personally experienced is more compelling than second-hand learning, all people are anchored to a specific set of views about money that vary wildly. For example, a person who grew up when inflation was high will invest less in bonds later in life than someone who grew up with stable prices.

An individual’s personal financial experiences represent maybe 0.00000001% of what has happened in the world, yet they constitute about 80% of how that person believes the world works. This explains why equally intelligent people can disagree profoundly on investing strategies, recessions, and risk tolerance. The widespread purchase of lottery tickets, particularly by low-income households who spend four times more than the highest income groups, is rationalized by buyers as paying for “a tangible dream of getting the good stuff that you already have and take for granted,” as saving often seems impossible for them. All financial decisions are justified by plugging available information into an individual’s unique mental model of the world.

Moreover, modern financial concepts like the 401(k) (created in 1978) and the Roth IRA (created in 1998) are relatively new. The entire concept of planning for a dignified retirement funded by individual saving and investing is only about two generations old. Thus, much of the “crazy” financial behavior observed is simply the result of people being “newbies” in a rapidly evolving financial game.

Luck and risk are siblings—forces outside individual effort that guide outcomes. The story of Bill Gates, who attended one of the only high schools in the world with a computer in 1968, demonstrates “one in a million luck”. His classmate, Kent Evans, who was equally brilliant and ambitious, experienced the opposite—”one in a million risk”—dying in a mountaineering accident before graduating high school and becoming a founding partner of Microsoft. Because the world is too complex for 100% of actions to dictate 100% of outcomes, one must believe in both luck and risk equally. To learn from success or failure, one must focus on broad patterns rather than extreme examples, as extremes are more likely to be influenced by non-repeatable luck or risk.

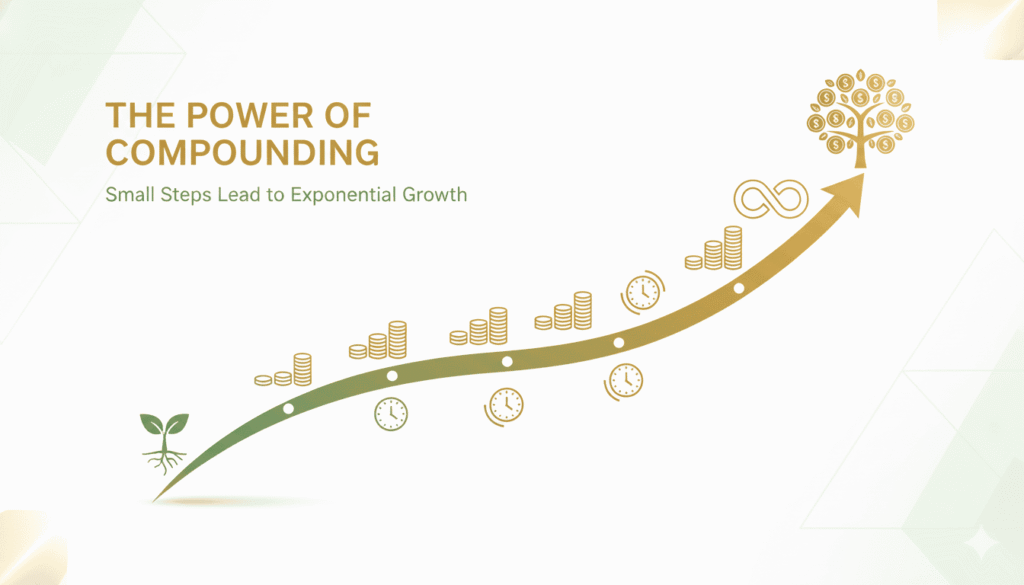

When discussing wealth accumulation, compounding is counterintuitive. If something compounds, a small starting base can lead to extraordinary results that seem to defy logic. Warren Buffett is a phenomenal investor, but the key to his success is longevity—being a phenomenal investor for three quarters of a century. The majority of his fortune ($84.2 billion of $84.5 billion) was accumulated after his 50th birthday. If he had started at 30 and retired at 60, his net worth would be 99.9% less than his actual fortune. Good investing is not about earning the highest returns; it is about earning “pretty good returns that you can stick with and which can be repeated for the longest period of time”. The book that would best explain Buffett’s success should be called Shut Up And Wait.

There is only one way to stay wealthy: “some combination of frugality and paranoia”. Getting wealthy requires optimism and risk-taking, but keeping wealth requires humility and the paranoia that what one has made can be taken away just as fast.

The stories of Jesse Livermore and Abraham Germansky, both ruined after the 1929 stock market crash, show that they were skilled at getting wealthy but equally bad at staying wealthy. Buffett’s longevity and compounding success is largely attributed to what he didn’t do: he didn’t use excessive debt, didn’t panic and sell during recessions, and survived long enough for compounding to work wonders. Rick Guerin, a contemporary of Buffett and Munger, was equally talented but was “in a hurry” and used margin loans, forcing him out of the game during a downturn.

A survival mindset prioritizes being financially unbreakable over achieving the biggest returns. The most important part of any financial plan is to assume the plan will not go according to plan. Room for error (or margin of safety) is the only effective way to safely navigate a world governed by odds, not certainties. Graham’s concept of margin of safety is summarized as: “the purpose of the margin of safety is to render the forecast unnecessary”. Room for error—be it a frugal budget, flexible thinking, or a cash reserve—is what gives an investor endurance, ensuring they can stick around long enough for low-probability, high-return outcomes to favor them. The dangerous flip side is leverage (debt), which pushes routine risks into “ruinous risk,” wiping out the chance for future success when opportunities are ripe.

Tails drive everything. Long tails—the rare, outlying events—account for the majority of outcomes in business and investing. For example, in venture capital, 65% of investments lose money, while 0.5% (about 100 companies out of 21,000) drive the majority of industry returns. This is true even for large, established companies: 40% of stocks in the Russell 3000 Index lose at least 70% of their value and never recover, yet the overall index shows spectacular returns due to a small handful of extraordinary winners. For an investor, success is determined by how one responds during the few periods of “sheer terror”—the 1% of the time when everyone else is “going crazy”.

Everything worthwhile has a price. The price of successful investing is not measured in dollars, but in volatility, fear, doubt, uncertainty, and regret. Many investors try to achieve high returns while attempting to avoid this price through market timing or tactical strategies, which rarely works. The irony is that by trying to avoid the cost, investors end up paying double. It is vital to view market volatility as a fee (an admission charge worth paying to receive market returns) rather than a fine (a penalty for doing something wrong).

The highest form of wealth is the ability to wake up every morning and say, “I can do whatever I want today”. Control over one’s time is the most reliable predictor of positive feelings of wellbeing, more so than salary or job prestige. Money’s greatest intrinsic value is its ability to buy time and options, conferring independence and autonomy.

The pursuit of wealth to signal success often falls victim to the Man in the Car Paradox: when people see someone driving a fancy car, they rarely think, “The guy driving that car is cool”; instead, they think, “If I had that car people would think I’m cool”. The attention is given to the possession, not the person.

The truth is that wealth is what you don’t see. Richness is a visible current income (e.g., affording an expensive car payment), but wealth is hidden income not spent—it is an option not yet taken to buy something later. The only way to be wealthy is to not spend the money one has.

Building wealth depends on the savings rate, not income or returns. Spending beyond a modest level of materialism is typically a reflection of ego approaching income. Therefore, a powerful way to increase savings is to increase one’s humility—caring less about what others think. It is critical to save without a specific goal, as savings without a spending target act as a hedge against the inevitable surprises in life and give one flexibility and time to think.

In financial decision-making, it is better to aim to be pretty reasonable than coldly rational. The mathematically optimal strategy is often too rigid and emotionally impossible to maintain. People usually want the strategy that maximizes how well they sleep at night. For example, the rational strategy of using high leverage when young might be mathematically superior, but it is “absurdly unreasonable,” as no normal person could emotionally withstand watching their account be wiped out and carry on undeterred.

Anything that provides the endurance necessary to stick with a strategy—like being passionate about one’s investments—has a quantifiable advantage, as consistent commitment puts the odds of success in the investor’s favor over time. The odds of making money in the U.S. stock market are 50/50 over one day, but 100% over 20-year periods (so far).

People are poor forecasters of their future selves, a phenomenon known as the End of History Illusion, where individuals underestimate how much their personalities, desires, and goals will change over time. Because a long-term plan will inevitably be challenged by changing desires, balance in life (moderate savings, moderate free time, moderate commute) encourages endurance and helps avoid future regret. The key is accepting the reality of change and moving on quickly, embracing the idea of “no sunk costs” regarding past decisions.

The economy is heavily influenced by stories. The massive $16 trillion loss in household wealth between 2007 and 2009 occurred not because tangible assets like factories or knowledge changed, but because the narrative about the stability of housing prices and the prudence of bankers broke. Furthermore, the more someone wants something to be true (e.g., a stock to rise 10-fold), the more likely they are to believe an “appealing fiction” that overestimates the odds of it happening. This willingness to believe anything when stakes are high is why people flock to financial quackery.

Additionally, pessimism is often more seductive than optimism because it sounds smarter and more intellectually captivating. Threats (pessimism) are treated as more urgent than opportunities (optimism), an evolutionary shield. However, pessimists often fail because they extrapolate present trends without accounting for how markets adapt and problems correct (e.g., predictions of running out of oil failed because the high price incentivized the invention of fracking). Also, destruction happens quickly (a war, a market crash), while progress (like the decline in heart disease death rates) happens slowly, making pessimistic narratives feel fresher and more immediate.

Finally, investors must recognize that bubbles form when the momentum of short-term returns attracts traders whose time horizons shrink, causing long-term investors to take cues from players of a fundamentally different game.

To make better financial decisions, the author offers several short, actionable recommendations:

In terms of personal finance, the author and his family prioritize independence—the ability to wake up and do whatever they want on their own terms. They maintain a high savings rate by keeping their lifestyle expectations constant, largely avoiding the “psychological treadmill of keeping up with the Joneses”. They made the “worst financial decision” but the “best money decision” by paying off their house outright, valuing the independent feeling over the potential rational financial gain from leveraging assets. Their strategy involves keeping a high percentage of assets in cash (“the oxygen of independence”) to ensure they are never forced to sell their low-cost index funds and interrupt compounding. Their success relies on a high savings rate, patience, and optimism, rather than attempting to outperform the market.